The Story of the Good Old Days

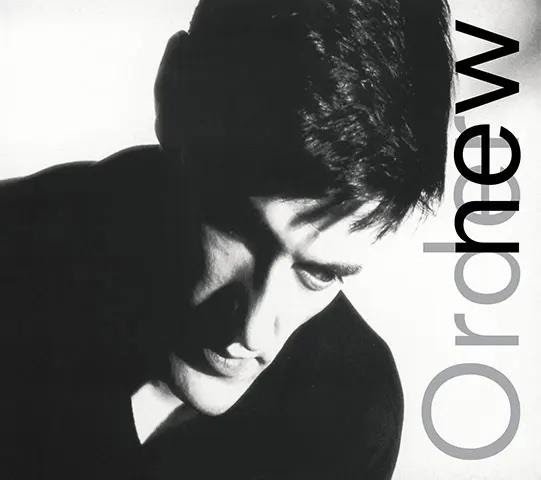

We’ve all heard it before and we’ve probably all thought it or said it to ourselves at one time or another. “Things were so much better back then.” I am particularly prone to this thought when it comes to music from the 1980s. I’m further confirmed by this bias when I see my own kids enjoying New Order or Depeche Mode or when I hear musicians they like today, like Conan Gray or The 1975 (which should really be named the 1985), producing 80s sounding songs filled with synthesizers and drum machines. Can it get any better? Never!

In schools, the stories of the good old days are everywhere. When I do strategic plans with schools one of my favorite parts of the process is doing empathy interviews with members of the community, and in large part, the faculty and staff. For the most part, these conversations are intentionally geared towards thinking about the future because that is what we are planning for, but we also ask questions about how the school has evolved over time, especially if we are talking to a long-standing member of the community, including younger alumni who have returned as teachers. And that is when we often hear the nostalgia for the past emerge.

Looking at research, there are, in fact, tremendous benefits of nostalgia in organizations. It’s not a terrible thing to look back and feel warm and fuzzy about the past and the way things were. . Because humans tend to have “selective memory retrieval” we end up with a cognitive bias that facilitates the realling of the more pleasant memories that produce dopamine and serotonin and other neurotransmitters in our brains. Reminiscing with another person can also create bonds and deepen relationships. This Harvard Business Review article on “The Surprising Power of Nostalgia at Work” suggests that nostalgia can actually create stronger teams, foster creativity, make work feel more meaningful and even reduce turn-over in staff.

Strangely enough, you can create feel-good memories that aren’t even real but elicit similar feelings of connection. At L+D, we sometimes play an improvised storytelling game with teams where we ask them to make up a shared memory with a partner. The game is called “Reminisce”. One year I was working with a strategic planning team, and we played this game at their first meeting. There was a pair that made up an elaborate memory of their days at an English boarding school together. Over the course of the year, each time the team would meet, the pair would sit together at the meeting and talk about their school days. I finally asked them how they had both ended up as parents at this school in CA. They laughed and told me “That was our shared memory from Reminisce! We didn’t even know each other before that first meeting.” They had bonded and the lines between what was real and what was imagined had blurred. That is the power of shared memory - even one that never happened.

The challenge of nostalgia comes when we are telling shared stories that may not be exactly true and those stories hold us back from what is actually happening or keeps us from evolving to what is needed in the future. Or they make us feel frustrated, resentful or angry. There may be kernels of truth in those narratives, but often they are a mere shadow of the real story that if we remembered, would fail to elicit all of those pleasant feelings.

A lot of what these teachers talk about in the empathy interviews when they are asked to remember the past is the change in the students they are teaching. Some of the comments I hear in these interviews fall into these types of patterns:

“Students aren’t as engaged as they once were.”

“Students don’t produce the same level of work as they once did.”

“Students aren’t reading as much so they can’t handle the harder texts like they used to. And their essays are less well written.”

“Students have no respect for teachers anymore.”

“We just don’t have the training or resources to manage all of the students with diagnosed learning differences like ADHD. We need more clarity on the students that are the right fit for this institution. We used to admit students we could teach.”

Similar stories play out about new generations of parents and new generations of faculty and staff and how things have changed and not for the better. Stories where we remember how parents showed up as trusted partners and how faculty and staff worked eagerly on after school committees and chaperoned dances with no question or complaint are probably not entirely true. They are also likely lacking context.

So what do we do when we find ourselves telling these stories, especially if our brain is telling us with certainty that they are true?

Get curious. It’s likely that what you are remembering is clouded by the passage of time and by our cognitive bias to the positive. What we are remembering will likely be the very best of the past but not the whole past. This doesn’t mean the story is untrue, but it might be less true than what we initially thought. Can you explore the story and parcel out what parts are true and what might be misrepresentations or misremembering?

Consider the context of the story. Back when I was in school and in my early days of teaching, very few students had diagnosed learning differences in schools, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. I’ve recently been interviewing some of my high school classmates for a project I am doing, and out of the 22 interviews I have done so far, five classmates have shared their adult diagnosis of ADHD. Four have shared their battles with depression in high school. The context that has changed is the speed at which we identify some of these challenges in students today, not that there is a lot more ADHD and depression now and it didn’t exist in the past.. Once again, part of the story is likely true, but maybe not as true as it was in our heads.

Shift your perspective to what is especially good about the current moment. What is actually better today - or maybe just possible that wasn’t possible a decade or two ago. For example, students are so good at working in so many different mediums today. They aren’t only writers, they also fluently communicate their ideas through film, music, and podcasts. The same neurotransmitters of remembering the positive aspects of the past can also be triggered if we think with warmth about the current moment. And someday, somebody, maybe you, will be looking back at this moment and remembering how good things were in 2023.

Remember that the good old days were not necessarily better than today for everyone. There are groups of people for whom the past was a lot less equitable, inclusive, physically safe, or even accessible. So consider remembering the past through the eyes of someone else. Was it so good after all?

It can be fun to look back at the past with fondness, but just be willing to admit that the past you are remembering is just a story.