Why We Still Care About Design Thinking

Estimated Reading time: 7-9 minutes

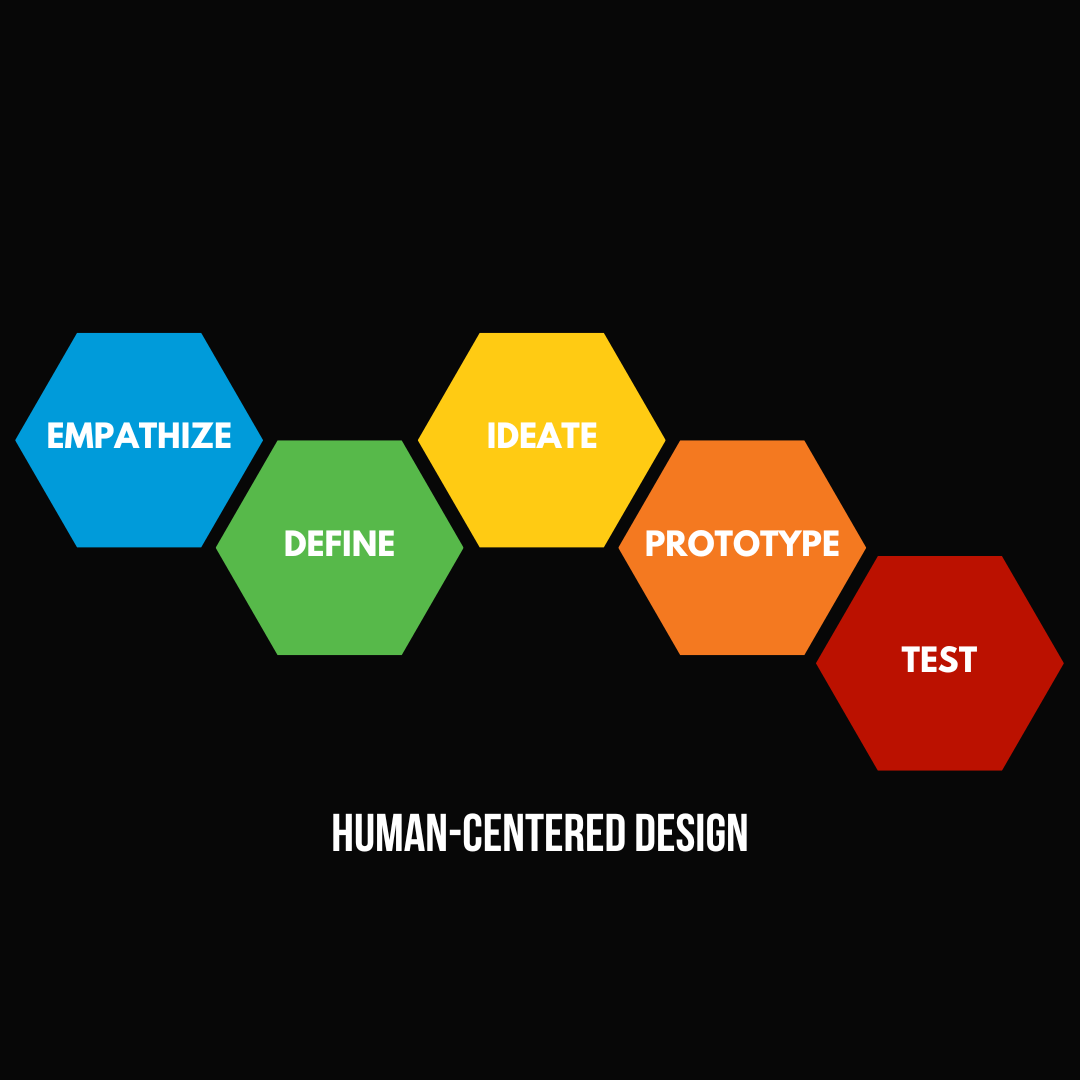

In 2014 as Leadership+Design, as it is known today, was forming, “Design thinking” was all the rage. Schools around the country were reaching out to bring design thinking to professional development days for faculty and staff, fab labs filled with 3D printers sprang up across campuses, a model of the Stanford d.School design thinking process (see the graphic to the right) often proudly hanging above the door frame. It was fun to pass out the post-it notes and sharpies and wheel in the prototyping cart filled with pipe cleaners, popsicle sticks, glue, duct tape and cardboard and watch educators of all different disciplines and roles build models of everything from the perfect wallet to the ideal faculty meeting. It was playful and interactive, which felt like the opposite of most professional development. I loved it!

In the years that followed, especially during the COVID years, the appetite for these types of workshops dwindled. Some schools never really got beyond the pipe cleaners and post-it notes and felt they had “checked the box” on bringing design thinking to their school. And part of that might have been the way “design thinking” was communicated (or miscommunicated) at scale to school communities. Myths of design thinking abounded: that every challenge had to follow the strict five step process, that solutions needed to be expressed in three dimensional models of cardboard and duct tape, or that “empathy” was a nice idea but that it didn’t produce real usable “data.”

With a few exceptions, L+D stopped doing stand-alone design thinking training workshops in about 2022, yet we never stopped prioritizing the type of thinking and work that comes from a deep commitment to design. We wanted to go deeper. Indeed, we use human centered design to partner with schools to set a strategy for the future, to build student centered daily schedules, to create advisory programs, portraits of graduates, systems of faculty growth and evaluation or to solve an infinite number of messy and ambiguous organizational challenges - goodness knows there has been plenty to work on in the past five years. By directly applying a set of habits and mindsets of designers to reimagine and create experiences for students and families, we have strived to build capacity for the groups with which we have worked on just about every project we have facilitated.

In 2025, I am more convinced than ever that human centered design is still the most powerful way to make deep, embodied, and co-created organizational change in schools. But it feels really different than it did a decade ago. It actually feels even more relevant with the rise in Artificial Intelligence which offers the questionable promise of solving any challenge with just a few well written prompts. I actually think we are going to need more design in the world, not less of it. We need to be paying more attention to the human experience and designing things that living, breathing yearn for and to design not just for these humans, but alongside them, with them.

To that end, this year’s newsletter theme is The Power of Design. It’s a chance for all of us at L+D to revisit some of our earlier beliefs about design and also to share how our thinking has evolved over 10 years of doing this work.

There are so many lessons that I have learned applying human centered design to work in schools, but if I had to choose my top four I would share the following as the golden nuggets that have lasted well beyond the post-its and sharpies (which, by the way, I still use and love).

Get close and get curious: Start with understanding human needs, motivations and behaviors by talking to people - human to human. There is a reason that we start every project we do with a school with one:one conversations. We have traditionally called them “empathy interviews” but what they really are is a chance to learn about the human beings in the community. These are not interviews where we have a list of questions that we run through, but rather an opportunity to get curious about the person we are with, to learn about their experiences, values, motivations, perceptions and behaviors. These are things you can’t get from a survey. Sometimes they aren’t quantifiable. But they are real and they are fascinating and they produce the most interesting insights. To really learn what people think, ditch the survey, get close and really listen.

Some of you may know the work of the lawyer Bryan Stevenson, who has worked to humanize incarcerated people and see them as greater than their worst act. Through his organization, the Equal Justice Initiative, he has enabled the release or reversed a death sentence of over 140 people. He talks about “getting proximate” to things that may feel hard and imperfect or that you might resist. He believes that only when we can get proximate can we walk the true path to justice and leverage our own humanity. Getting close can sometimes mean having our own beliefs and assumptions challenged, and it is how real change is often made.

Explore many possibilities: Don’t be afraid to ask, “What else is there?” Sometimes in schools we get a good idea and then we spend a lot of time developing it and making it pretty and perfect only to see this new initiative have lackluster results. Sometimes it’s gone within a year or two. I recently read an article by Dev Patnaik, the CEO of the design strategy firm Jump Associates, and the author of the book Wired to Care. He shared that this fixation on one good idea is the death of many aspiring companies or even established corporations trying to launch The Next Big Thing. Patnaik talks about the importance of “multiplicity,” the act of exploring and testing multiple ideas and not settling on just one. He writes, “Designers have always prized multiplicity. Ask a graphic designer to create a new logo, and they'll come up with several different options. Ask a product designer to reimagine a toaster, and they’ll invent fifty new ways to heat bread.”

A good design process will often surface an opportunity space but identifying and investing time and money in one possible solution may not lead to the results you expected. Asking “What else might we do?” might feel, in the moment, like a colossal waste of time, but as Patnaik writes: “Multiplicity isn’t about hedging bets or indecision. It’s about building a portfolio of real contenders so you’re not left with nothing when the first one falters. It gives leaders resilience, not just optionality. It creates the conditions for adaptation in a volatile environment.”

Build to Think: Make your ideas visible and testable. The post-its, sharpies, and duct-tape were never meant to be the lone tools for your ideas. Often the best prototypes I saw were experiences that schools were testing and piloting among small groups or on a smaller scale. Their long term vision was to design a three week immersive program for the entire high school, but they tested a week-long experience for the sophomore class. This was their “high fidelity” prototype. Clear visible thinking meant that you could get a lot of feedback quickly. And the team in charge of the design was able to create a few options (see multiplicity above) to test and validate. In the creation of the different prototypes, they also continued the divergent process of generation of several ideas. They were building to think.

All of this prototyping will more likely lead a team to actually do something with their ideas and to have a bias to action, to create something not just in theory but in practice. I have seen committees come up with some brilliant things on paper, but when put into practice are not feasible, desirable or viable. When you build to think, you are testing things on a small scale and finding out whether or not it is going to work. For example, prototyping and testing a new advising program with one or two groups or a grade level is so much more manageable that trying to roll it out to the whole school. And it allows you to try something and not wait for everyone to get on board and get trained to execute. Just as importantly, you can learn so much from those early iterations that will save time and money down the road. It feels good to do something. It builds momentum and energy. People around you will ask, “What’s going on over there?” And before you know it, you are moving your idea to scale without all of the hand-wringing and whisperings of “Will it work?” You already know - it does. So build, test, iterate.

Co-create: The work is best when you are doing it together. At the heart of human centered design is the idea of radical collaboration. Design is best when a team of people comes together whose members might have expertise in different areas and industries or, in the case of a school, come from different disciplines or divisions or roles. These diverse perspectives often help the team to see a problem from different angles and generate many possibilities for solutions. And, when the skills and perspectives of all team members are valued and put to good use, teamwork is just more fun. Creating solo can be very efficient, and collaborating with chat GPT can open up some new angles, but creating something new with a team of colleagues who are passionate and invested in the project, working through the inevitable highs and lows of both the group dynamics and the collaborative process, and high-fiving the moment when great ideas become reality, well that is what being human is all about!

If you are excited about what you are reading here and are ready to revisit the power of design in your school this year, we will be here to harness your enthusiasm. All year we will be writing about design and helping our readers to fall back in love with using a human centered design process in their work. And if that is not enough, we are launching a national design challenge. The L+D Expedition - that YOU can join that will enable a team at your school to take a challenge they want to work on - a strategic question or institutional priority - and get some real traction on it. We will guide your team through the design process and help you to produce and test a prototype or two. Your submissions will be reviewed by a jury of industry experts who will recommend five teams to participate in a pitch presentation in Seattle on February 27, adjacent to the NAIS Annual Conference with the chance to win cash prizes. But the sweetest prize is the opportunity to build your team’s capacity in the habits, skills and mindsets of human centered designers. Teams are registering now, so check it out and register a team!