Against Certainty

Estimated Reading Time: 4-6 minutes.

This is a note to people in the middle of something that feels unresolved, uncertain, or, at its best, still emerging.

You might be leading a design process that doesn’t seem like it will land cleanly. You might have built a prototype: a schedule, a curriculum, a plan to double down on athletics, the long-awaited reimagined flow for carline. And now, it all feels vulnerable, exposed to critique, judgment, or even outright failure. You might be sensing pressure to finalize work, even though you know there’s more to learn.

If you’re feeling that pressure to stick the landing, this is for you.

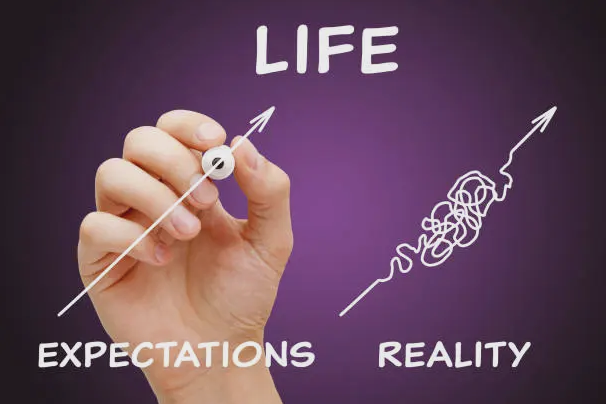

Design work often carries an implicit promise: with the right process, our learning will create clarity and certainty about what to do next. We expect a cleanliness and closure, the right answer, and confidence that we’ll unearth a readiness to move forward.

This expectation doesn’t always match the reality of the work.

At Leadership+Design, this is the time of year when process reaches an apex and this tension is most visible. Strategic planning clients are beginning to draft initiatives. Our fellows are moving forward in their leadership projects. Teams in the L+D Expedition are approaching their final submissions. Their work quite literally will be judged. Across contexts, learning is starting to take shape, and that shape brings with it that pressure: to get it right.

Let’s Not Confuse Learning with Certainty.

Not all of our work holds the same relationship to certainty.

Some parts demand it. Contracts, enrollment projections, and staffing agreements: these can demand as much certainty as we can muster. In these areas, decisiveness is part of our leadership responsibility.

But program design, schedules, curriculum, and strategic initiatives: this work is fundamentally different. It’s developmental, and our most accurate understanding is formative over time. These efforts require learning before closure, and closure is just a transition to a new phase of learning as we observe and learn from the response to plans set in motion.

Trouble–and pressure–builds when we as designers position developmental work with the spirit of summative certainty. This pressure can narrow our willingness to move forward and erode the broader culture of learning we say we want to cultivate in our organizations, but are sometimes hesitant to model in our work.

Take schedule design as an example.

We often feel pressure to present a schedule as a finished artifact. Behold the coherent, defensible, and optimized artifact of our future everyday experience. We want schedules to work to perfection on paper because the cost of being wrong feels high.

But some of the most essential learning in a schedule doesn’t surface until we set it in motion and observe how the community leans into the design principles we carefully used to shape that prototype. Can we build prototype spaces inside of a schedule – ribbons that we can fill with community time, What I Need, or clubs - spaces that can shift and shape as we learn how we live into them best?

This means casting out into a schedule - or an initiative program or plan - with the spirit of learning and exploration that will serve us best.

Designing at the Speed of Learning

Reframe the pressure of “is this right?” to ask a question that will give you traction: “what might this help us learn?”

We can move forward with intention without waiting for certainty and knowing that forward movement will surface a constellation of learning about the people, culture, and systems that surround our work.

And this is the work of prototypes and the possibility of reframing much of what we create or implement as prototypes. When we design a new program, is the prototype the plan we sketched out on a whiteboard? What ends up in the course catalogue? The first or fifth year of the experience?

A design needn’t be a finish line. A design is something real enough for us to learn from.

That learning rarely arrives as a limitation. It’s often even deeper insight into relationships, assumptions, constraints, and possibilities we couldn’t have understood without setting something in motion.

Leadership here is less about resolving everything at once and more about cultivating a collective understanding of what needs action now, what needs additional attention, and what learning needs more time to unfold all without halting motion forward.

Design work shapes systems and experiences, and it shapes the designer as well. As we try to change something for the better, our understanding of what better means often changes as well. Our sense of ourselves as leaders, collaborators, and learners changes, too.

Rarely does uncertainty disappear as we move forward. Instead, it transforms.

The goal of design is to move forward to a place where we can continue learning.

If You’re Stuck in the Middle, Consider Four Moves

Change Altitude

If an entire evaluation system feels stuck, the next step might not be to delay movement until we can perfect it, but perhaps the next step isn’t to perfect it, but to reimagine the one-on-one conversations within it. If a large structure feels overwhelming, movement at a different scale can restore momentum without pretending the learning is complete.

Lower fidelity

If the work feels high-pressure, and all of the details seem like they’re blocking forward movement, loosen the draft. Offer up a lower-fidelity (or rougher) prototype and invite feedback. Most often, less refined work invites learning and exploration, and more polished work invites judgment.

Separate what needs certainty from what needs learning.

Name explicitly which parts of the work must close, and which are allowed to remain open. This alone can relieve pressure and restore momentum.

Don’t move forward to validate. Embrace forward movement as learning.

Advance the work not to demonstrate correctness, but to surface information you couldn’t access before. Let movement be an act of inquiry.

If You’re In This Space

If you do find yourself in the middle, feeling stuck in a space with work you can’t yet close: this is a space we love. It’s where the most learning about self, community, and culture emerges, where our work as designers becomes most alive.

We’re always excited to think alongside anyone navigating this sort of middle. Drop us a note. We’d be happy to explore.